- - - Brought to you by: The Investigative Project On Terrorism

Kevin James walked out of the Supermax penitentiary less than two months ago, where he was imprisoned for plotting a series of jihadist attacks against Southern California military targets and synagogues. Since then, he has repeatedly lied to those supervising him in a halfway house – lies about how many cell phones he had, about where he would go outside the house.

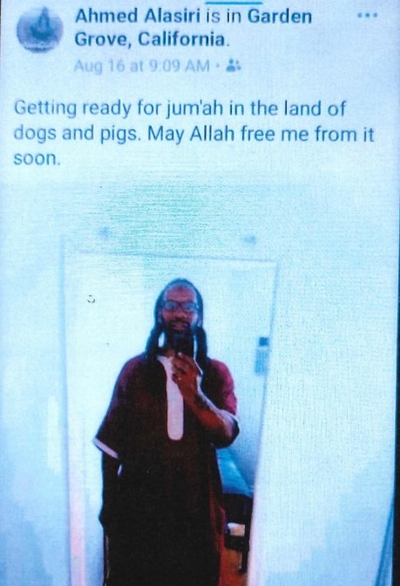

He already has been fired from a job for spending too much time on his phone. He posted a picture online describing himself as living "in the land of dogs and pigs. May Allah free me from it soon."

For those reasons and more, prosecutors and probation officers want a federal judge to impose additional restrictions on James while he is on probation. Those restrictions include an electronic monitor to track his movement and the power to search him, his home, and his belongings at any time without a warrant.

Those conditions were temporarily imposed on James in a Sept. 11 order signed by U.S. District Judge Cormac J. Carney. A hearing is scheduled for Oct. 7 to determine if they will be made permanent.

"Defendant's post-sentence behavior eliminates any doubt that the conditions requested are essential to protect the public and deter the defendant from engaging in any further criminal activity," Assistant U.S. Attorney Dennise Willett wrote in court papers filed Monday.

James's case represents an emerging challenge law enforcement faces as dozens of people convicted of terrorist crimes since the 9/11 attacks complete their prison sentences. Unlike sex offenders or domestic violence offenders for whom Congress has enacted specialized mandatory conditions of supervised release, there are no uniform standards for restrictions on a released terrorist during the subsequent probationary period. And there is no notice given to local communities, alerting them when a terrorist is released.

James was serving time in a California state prison for armed robbery when he formed the radical Islamic group Jam'iyyat Ul-Islam Is-Saheeh (JIS), "a Muslim extremist group who recruited others to carry out violent attacks ... [against] U.S. military locations and Jewish synagogues," Willette wrote. He designed the plot and recruited others "even while his freedoms were restricted in state custody."

In 2007, he pleaded guilty to conspiring to wage war against the United States through terrorism. Two accomplices robbed a dozen Los Angeles area gas stations to fund the attacks. Prosecutors say that James drafted a statement to be released after the first attack, saying it was "to defend and propagate traditional Islam in its purity" and warn Muslims to stay away from "[t]hose Jewish and non-Jewish supporters of an Israeli state."

He was sentenced to 16 years in prison, and received credit for time served since transferring to the federal prison system. He was able to shave more than a year off that sentence for good behavior despite at least two disciplinary episodes that led to his transfer out of a general population prison in Terre Haute to the Supermax penitentiary in Florence, Col.

In Terre Haute, James served with another convicted Islamic terrorist, John Walker Lindh. James participated in an unauthorized group activity with a cadre of Muslim inmates and refused a direct order from security staff to disband.

James said the gatherings were just "classes."

Lindh challenged the Bureau of Prisons, saying that prohibiting the meetings violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. A judge discounted Lindh's terrorist background and described his time in prison as having, "merited him a classification of low security."

Lindh was released in May. He also received time off of his 20-year sentence for good behavior. It is a credit that can trim up to 15 percent off the sentence of any federal felon. It is unclear whether anyone has considered re-examining that structure to take into account the unique threats posed by those convicted for plotting violence or taking up arms against this country.

In another run-in with prison authorities, James had a heated exchange with prison staff in 2012 "causing other inmates to gather around." He then argued with a security officer, asking, "who are you to tell us to be quiet?", and calling the staff "cowards" who hid behind their uniforms.

James's clear display of animosity toward authority confirms a 2003 federal government report's finding on prison radicalization and the type of inmate most susceptible to acting out violently when released.

A hearing officer found that James "created a risk to the institution security, good order, and the safety of staff, inmates, others, and/or the public safety."

He left prison for a halfway house on July 30. Since then, the brief said, James violated policies at least a dozen times. He was ticketed by the California Highway Patrol for driving without a license in a car he didn't disclose as required to the halfway house staff.

The added conditions on his release "are essential to preventing any attempts to commit similar crimes in the future and address the reemergence of any extremist views early on," the government brief said.

"The court and society have a strong interest in ensuring that defendant does not reoffend - an interest that is served by verifying that defendant is not expounding extremist propaganda to recruit others to commit terrorist acts, contacting others with extremist views to engage in terrorist acts, reviewing terrorist material that provide blueprints for criminal activity, and associating with others who are members of JIS, during his supervised release term."

One of James' co-defendants, Hammad Samana, is already out of prison. A second, Gregory Patterson, is scheduled for release in March. Co-conspirator Levar Washington, is in FCI Lewisburg, a maximum security facility in Pennsylvania, and not scheduled for release until 2030.

James "has shown he cannot be taken as his word that he will abide by the terms and conditions of his supervised release---he must be consistently monitored for compliance," the government brief said. He lies about where he intends to go; he lies when confronted about his conduct; and he lies about the underlying facts that result in his discipline."

James's case is not unique.

Every time a terrorist is released from prison, prosecutors and probation officers must ask a judge to modify the conditions of release. There is no guarantee that the district court will grant such requests.

As the number of terrorists completing their sentences increases, there also are questions whether probation officers have sufficient resources to monitor potentially violent felons like James.

Another terrorist walking free is not a comforting thought for a society that just recently honored the memory of those lost on September 11, 2001 when radical Islamic terrorists attacked us.

Until there is a viable post-release supervision program designed for terrorists, the threat will only increase.

IPT Senior Fellow Patrick Dunleavy is the former Deputy Inspector General for New York State Department of Corrections and author of The Fertile Soil of Jihad. He currently lectures a class on terrorism for the United States Air Force's Special Operations School.